I was always told that after my Pop, Frederick Otho Alchin (1917-1998) returned from active service during the Second World War, he had a desire to never go anywhere too far from home again. I don’t think that being a soldier defined him as a person but it certainly influenced his identity. Like most returned service men, he didn’t talk much of his experience to his family and the few details that I have of his time as a soldier were gathered from close examination of his personal records as well as those maintained by the National Archives in Canberra. Fred was one of four Alchin brothers who enlisted for service in the closing years of the Second World War. While Fred’s war experience may not be considered epic by most war standards, it is certainly worth chronicling.

In August 1940 Fred was accepted into the Citizens Military Forces (CMF). The Citizens Military Forces (now known as the Australian Army Reserve) was a citizen’s militia that had an obligation to serve in Australia and its territories, not in foreign countries. The duty of international defence, to fight overseas, fell on the Second AIF (Australian Imperial Force) that was made up of volunteer soldiers. As part of the Citizens Military Forces Fred was first assigned to the 7th Light Horse Regiment. Fred ‘marched in’ for a prolonged period of training in Tenterfield, New South Wales in December 1941 but six months later the 7th Light Horse Regiment was reorganised for modern warfare and became the 7 Motor Regiment under the AIF, which meant that now, along with changes to the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Act (1943), Fred was being prepared for overseas conflict, probably not what he had expected when he initially signed up. Again, just three months later in November 1942 Fred was transferred from the 7 Motor Regiment to the 3rd Australian Armoured Division (as part of the headquarters company).

The 3rd Australian Armoured Division was a light to medium tank unit. It was while assigned to this unit that Fred returned home to marry Isabell Emma Whittington on the 3 Dec 1942. Eight and a half months later their first son, Donald Alchin was born. The colour patch of the 3rd Australian Armoured Division, a black hexagonal patch with grey tank and a grey border can be seen on Fred’s shoulder in a photo capturing what would have been the first meeting between Fred and his new son.

Back in Tenterfield for training, Fred received an injury to this lower jaw and right arm in February 1944 from grenade shrapnel, and spent 16 days at, or attending to, the camp hospital. His service forms tell that an investigation into the incident was not held. In March, he and many of his fellow troops marched out of Tenterfield to the Jungle Warfare Training Centre in Canungra, Queensland. Training was ramping up and the troops began to be reorganised for what many suspected would be active duty overseas. Fred hinted of these suspicions in a letter home to his mum on mother’s day 1944, telling her “don’t write ‘till you hear from me again”. Five days after sending this letter, Fred was transferred to the 2/23rd Australia Infantry Battalion, the unit that Fred would remain assigned to until the end of the war. This battalion, like most others was divided into five sub-companies, Headquaters Company, and companies A, B C and D. In the photograph below it appears that Fred was initially part of the Headquarters Company (HQ).

This battalion, along with others, sat under the 26th Brigade which was being prepared for an operation in Borneo known as OBOE 1. This operation was the first in a series of six OBOE missions in Borneo and its objective was to recapture the small island of Tarakan off Borneo’s east coast. A number of strategic justifications were given for the mission which included securing the Tarakan airstrip which could be used in follow up missions, to disrupt the Japanese oil supply from the small oilfields on the island and to help liberate what was previously Dutch territory while clearing the Japanese from the island. As noted by the Australian War Memorial website, the operation was “widely criticised, both at the time and since, as a needless waste of…lives…against an enemy who posed no threat.” The operation was, however, critically important to those who fought and died during it.

On 1 September 1944, the unit moved to Cairns via rail to take part in amphibious training at Trinity Beach, ahead of the upcoming operations. On 10 March 1945, the troops were advised that they should prepare for embarkation for overseas service. Fred and the troops who were to make up the OBOE 1 force left Townsville in April 1945 on the US Army’s transport ship, the General H.W. Butner. This transport has been described as a ‘hell ship’, and at 5:30pm every night, the 5000 passengers on board were forced to retire to the lower decks where the men slept in cramped conditions during the ten-day voyage to Morotai, a forward base in Indonesia. Here the troops camped for a week in wet and muddy conditions, completing further training until they bordered the transport ships that were bound for Tarakan Island. Fred boarded the United States Landing Ship Tank (LST) number 466 which was the transport for the C and D companies of the 2/23rd Battalion, so it appears the Fred had been moved from the battalions Headquarters Company to that of either C or D. These transport ships were crowded with vehicles and supplies and the troops had limited space to move or sleep, most had no bunks and a short supply of water. The toilets hung over the edge of the ship and many at the breakfast table were suspicious of the ‘sea sprays’ that crossed the decks in windy weather.

On the morning of 1 May 1945, the amphibious landing at Lingkas Beach on Tarakan Island commenced after heavy bombardment of the beach and inland areas. The beach was divided into different zones, with Fred’s 2/23rd Battalion to land at the right flank, on ‘Green Beach’. On board the LST transport ships the troops embarked into smaller amphibious armoured landing vehicles known as LVT 4’s or ‘Alligators’. Each open-topped ‘Alligator’ held 24 men plus crew. The deep blue mud and embankments of Lingkas Beach caused trouble during the landing and the first troops of the 2/23rd Battalion had to scramble over the front of their ‘Alligators’ and drop armpit deep into the mud rather than exiting via the vehicles rear ramp. The original plan had the ‘Alligators’ caring troops a kilometre or more inland, however the difficult beach conditions meant that troops were forced to get out and go by foot from the water’s edge. Later, the following transport ships drove hard at the muddy beach, grounding themselves and releasing their mechanical cargo. Many vehicles got bogged trying to disembark, while the landing ships themselves were stuck in the dropping tide for lengthy periods. Fortunately, there was no Japanese opposition to the landing or many casualties may have been expected in the ensuing traffic jams on the beach.

The 2/23rd Battalion spent the first four days capturing objectives and clearing the enemy on the right flank. On 5 May, the battalion, which had stalled in its capturing of Tarakan Hill was relieved by another unit and the 2/23rd Battalion was moved to the Tarakan airstrip to help defend the area which was in the process of being captured by the 2/24th Battalion on the left flank. According to Fred’s discharge papers, his role during service was as a MMG and tank gunner. The role of ‘tank gunner’ was probably a legacy role from his time in the 3rd Australian Armoured Division and not one he was likely to have done while on Tarakan. MMG refers to Medium Machine Gun and on Tarakan probably means he was primarily a Vickers machine gun operator.

Once the airstrip was secured, the 2/23rd’s next objective was to clear the surrounding ridges, namely two features known as Tiger and Crazy Ridge. On 9 May, after nine days on continuous engagement with the enemy, and 13 days with poor to no sleep since leaving Moratai, the 2/23rd were relieved for a few days, during which they commenced patrols around the airstrip, the operation that perhaps best defined the method of fighting on Tarakan Island, and one which the Australians became very good at. Patrolling involved small groups of men heading out into the jungle looking for the enemy and defusing booby traps. Typically, a scout would lead the party, followed a little further back by a second scout then one or two groups of up to three men, separated by a few meters. When the patrols were not stumbling upon booby traps or Japanese soldiers hiding in pillboxes (bunkers), they were being snipped at by hidden gunmen. The Japanese excelled in snipping in the jungle, and the fear of being taken out by a silent assassin put enormous stain on the nerves of the patrolling soldiers.

The troops on Tarakan were closing in on Fukukaku, where most of the Japanese were gathered at what was their centre of operations on the island. The fighting for the 2/23rd Battalion intensified in the last weeks of May as they cleared a featured known a Margy, a ridgeline along the way to Fukukaka. Capturing and clearing Margy was to be the 2/23rd’s most intense and exhausting missions on Tarakan.

By 16 July, Fukukaka (the Japanese headquarters) had been cleared and the ‘mopping up’ phase began, with each battalion given a sector on the island from which to conduct patrols and round up or eliminate any remaining enemy. The 2/23rd’s sector (shown on the map below) was a central chunk of the island, between the airstrip and the Juata oilfield. During the mopping-up period the 2/23rd were also engaged in pursuing the enemy north. The island of Tarakan offered nowhere for the Japanese to retreat or escape to, so most were killed rather than captured or evacuated.

By 28 June the Tarakan airstrip was finally repaired and ready to receive aircraft. The original plan had assumed that the construction crews would have completed this objective by mid-May at the latest and the delay now questioned the strips usefulness in follow-up campaigns. When the first aircraft landed they found the strip still soggy and littered with bomb craters.

By 9 July, with combat missions all but over, a period of training and recreation began. Short courses and lectures were offered to troops and they were encouraged to think about what they might like to do when they return to civilian life. Several wood workshops were set up on the island and battalions got busy improving their camps and local amenities. The sombre task of burying the dead also took place in this period.

The news that a new weapon, an atomic bomb, had been dropped on Japan on the 6 August and again on the 9th filtered through to the troops on Tarakan and on the 15 August the news was confirmed, the Japanese had surrendered and the war was over. Troops now had to wait for their turn to demobilise and leave for home, those who had served longer got to leave earlier.

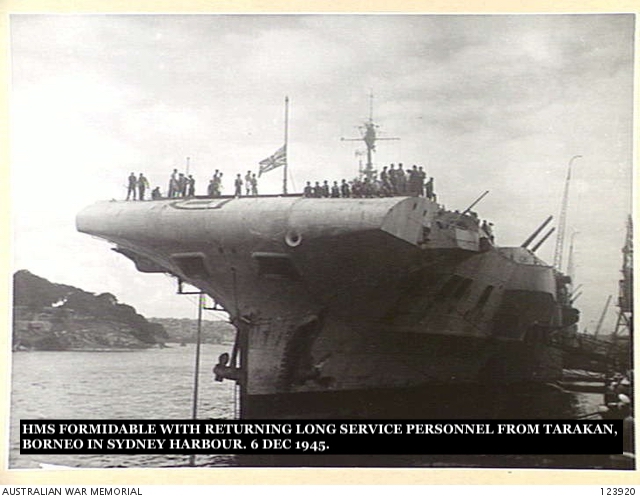

Among Fred’s paper records was a small information card for a ship called the HMS Formidable, suggesting that Fred returned home via this British aircraft carrier. The HMS Formidable was bordered by a small number of 2/23rd Battalion soldiers (along with contingents from many other units on Tarakan), on 26 November 1945. The ship returned to Australia, after picking up additional soldiers at Morotai, pulling into Sydney Harbour on 6 December 1945.

According to Fred’s military papers, he was officially discharged on 13 December 1945, after which he returned the Dalton area where, true to his wishes, he never really left. The only surviving oral account from Fred’s time in the war, at least that I have heard is this; while in service Fred told that one day he felt a shock, pulled up sick and had a feeling that something was wrong. Releasing that he himself had not been injured his thoughts immediately turned to his twin brother Robert ‘Bob’ Alchin (1917- 1996). Fred told that he knew something had happened to Bob, and indeed it had. Bob, who was on active service elsewhere had received a bullet wound to his arm that day. Fred, according this oral account, knew his brother had been shot and felt ill for days after the actual injury to Bob had occurred.

After returning to civilian life, Fred worked for a number of years on the Bloomfield property at Blakney Creek near Dalton, as a station hand with his young family. After the work dried up he got work on the railroads, a job that was common for returning soldiers to take up. I have the sense that Fred’s work on the railroads, and the friends he made while working on them, meant more to him that this time in Tarakan, however his time at war must have surly left its mark and maybe it meant more to him than he ever led on. ANZAC Day, of course, was a big day and a big deal for him but I doubt any game of two-up played upon return could compare to those that were played in the tropical humidity in the forests of Tarakan.

*Header Image: A group of men gathered around spinner during game of two up on Tarakan Island, Borneo, by Harold Freedman, Australian War Memorial Collection (ART26781). Image Cropped. Imager is licensed under CC BY-NC.

See also: Alchin family Tree

Sources:

Fred Alchin, personal papers.

Fred Alchin, paper records (barcode 5662162), National Archives of Australia, Canberra

Tarakan; An Australian Tragedy, by Peter Stanley

Mud and Blood: Albury’s Own, Second twenty third Autralian Infantry Battalion ninth Australian Division, edited by Pat Share.

Second World War Official Histories, Second World War, Series 1 – Army, volume VII – The Final Campaigns, chapers 17 – 18, by Gavin Long. Available at https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417312

2/23rdBattalion Way Diaries, 2ndAIF, March – December, 1945. Available at https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1360744

Leave a comment